FORINT: When windows aren't windows

The first in series about forensic intelligence and methods we *should* use

Forensic science* has the ability and capacity to be an active participant in investigations, rather than its traditional passive role. Too often, the evidence is collected, submitted to the laboratory, and the investigators wait for results, creating a lag between when the information is needed and when it is made available. Obstacles to forensic service providers being actively involved in investigations include organizational cultural norms, operational resources, sworn and civilian human resource issues, and media-driven expectations of outcomes.

Intelligence, as a formal product of information analysis, essentially reduces uncertainty.1 Uncertainty comes from asymmetric information, whether it be terrorists secretly plotting an attack or criminals clandestinely surveilling a bank to rob. While traditional intelligence analysis is forecasting, forensic science* and criminal investigations are reconstructive and this alters which methods can be and how to improve investigations.

Forensic intelligence (FORINT)2is not a new concept but one that has been misused in the classic sense of intelligence and is under-utilized in criminal investigations. What has been characterized as forensic intelligence in the literature is largely forensic support to crime analysis, like patterns of drug seizures or other crime maps (that’s criminology). The benefits to using actual forensic intelligence actively in investigations by shifting forensic results, even if preliminary, to the front-end of the criminal justice system, are reduced wrongful arrests and convictions, more efficient use of policing resources, and stronger cases for adjudication.

Let’s get our definitions straight

Information is anything that can be known without regard for how it was discovered or learned. By contrast, intelligence is information that meets the expressed needs of government and has been collected, processed, and narrowed specifically to meet these needs. Thus, all intelligence is information but not all information is intelligence.

With the growth of both crime analysis and intelligence analysis, it is important to distinguish the two. The difference between crime analysis and intelligence analysis is that:

Crime analysis focuses on analyzing a series of crimes—most notably homicide, assault, robbery, burglary, and auto theft—that have already occurred, with the intent of apprehending the offender(s) and deterring continued criminal acts.

Intelligence analysis (in policing and FORINT) assesses diverse types of information that suggest potential criminality—such as suspicious activity reports, tips, and leads—for the purpose of identifying a criminal threat that is typically trans-jurisdictional in nature, with the purpose of intervening to stop the threat. The goal of intelligence analysis is to offer approaches to intervene and mitigate or remove the threats at the strategic and tactical levels.

Intelligence methods: Non-Windows

Here we go. The intelligence community (the IC, for short, which is a pretty cool nickname) uses structured analytic techniques to help mitigate biases in intelligence analysis. Sound like something forensic science* should use? Yup. Read my chapters footnoted earlier.3 Plus, this is the first in a series on FORINT, so keep reading. Thanks, by the way.

A window operating in a metaphorical capacity lets me into all sorts of imaginative viewpoints. A window equals a kind of perspective, but can act as an entranceway, or an escape hatch. It constitutes a way to let light in while inhibiting most of what else exists outside of the constructed space from coming inside.

The Johari Window

We go into conversations assuming what the other person(s) knows. Sometimes, we get this wrong; we don’t know what they know and, sometimes, we don’t know what they don’t know. This can make conversations awkward, at best, and disastrous, at worst.

The Johari4 Window was created by psychologists in 19555 and is used primarily in self-help groups and corporate settings as an exercise in self-evaluation. I know, I know, but please keep reading. The participants picked a number of adjectives from a list, choosing ones they feel describe their own personality. The subject's peers then get the same list, and each picks an equal number of adjectives that describe the subject. These adjectives are then inserted into a two-by-two grid of four cells.

When used in critical thinking and intelligence analysis, the Johari window acts as a check against assumptions or implicit biases and forces an explicit recording of who knows what and what that might mean.

Famously, former US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld caught flak for saying there were “unknown unknowns.” Known unknowns are risks you are aware of, like when your flight is canceled. Unknown unknowns, however, are risks that come from situations that are so unexpected that you haven’t even thought of them. He was right about that, at least.

In risk assessment6 or other types of intelligence activities, examining your blind spots helps identify areas where you or your organization or your investigation might be unaware of potential risks due to lack of information, feedback, or situational-awareness. It also forces you and your colleagues to have a conversation about what you know, what they know, etc., etc. and then record it for posterity. Try it sometime.

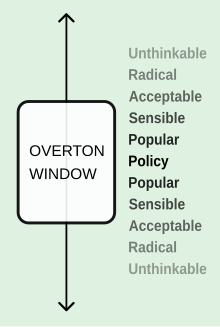

The Overton Window

Also known as The Window of Disclosure, the Overton Window is the range of things people are politically allowed to talk about at any one time. The big idea is that it moves… it can get bigger, smaller, shift left or up or whatever. The term comes from Joseph Overton, a former VP at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. He suggested that an idea's political viability depends on whether it falls within a socially acceptable range, not just on politicians' personal views. This "window" defines which policies a politician can support without seeming too extreme for public approval at a given time.

“The most common misconception is that lawmakers themselves are in the business of shifting the Overton window. That is absolutely false. Lawmakers are actually in the business of detecting where the window is, and then moving to be in accordance with it.”7

Arguably, the Overton Window suggests that leaders are really followers and the rest of us determine the types of policies they’ll get behind.

If you’re interested in policy change in your organization, keep the Overton Window in mind. If the policy (like protocols, evidence submission, quality issues, etc.) are outside the window frame, as it were, starting a conversation about it with leadership might be difficult. Building broader support is important because you’ll give your leadership more reason to at least talk about it.

What the heck does the Overton Window have to do with FORINT? If there’s an assumption that everyone holds dear or there’s a hypothesis that someone just won’t even consider, that’s their Overton Window. You need to figure out how to shift the window to have that conversation; even if you’re ultimately wrong, you won’t know until you can have that discussion.

Why you should care

Forensic services often take a backseat in their relationship with law enforcement, operating in a passive, reactive role. We wait for evidence to come in, process it, send out reports, and that’s the end of our involvement—like a simple transaction. This structure, where policing takes precedence over science, keeps forensic science* stuck in a low-priority position on the organizational chart instead of being a full partner in investigations.

So why isn’t forensic science* actively integrated into criminal investigations? Several barriers stand in the way:

Organizational barriers: Forensic experts are typically only called in for complex or high-profile cases, rather than being consistently engaged in intelligence efforts.

Individual barriers: Many forensic professionals don’t see the value they could add to intelligence sharing, overestimate the effort required, or simply don’t know how to contribute effectively.

Collective barriers: These issues add up, preventing forensic data from evolving into actionable intelligence.

Additional challenges include:

Intelligence analysis and reporting not meeting traditional forensic quality assurance standards required for accreditation.

Forensic scientists’ hesitation to share preliminary or ‘soft’ information, fearing it could be misused in court.

A lack of awareness among forensic labs about what law enforcement actually needs.

Outdated IT systems that aren’t designed for intelligence sharing, with limited connectivity and integration.

Addressing these obstacles is crucial for developing a model that fully integrates forensic information into the criminal intelligence process. Which we should do, honestly, because forensic science* has a lot to contribute to the front-end of investigations.

Lowenthal, M.M., 2022. Intelligence: From secrets to policy. CQ press.

I know I’ll get in trouble for coining FORINT but, honestly, I don’t care. It’s about time. Also, some of this appeared in two chapters I wrote previously, so it’s been out there already: Houck, M.M., 2020. “Front-end forensics: an integrated forensic intelligence model.” Science Informed Policing, pp.161-180 and Houck MM. 2020. “Improving criminal investigations with structured analytic techniques.” Science Informed Policing, pp. 123-59.

Or email me and I’ll send you personal use copies.

The name Johari is a commingling of the creators’ names. Cute.

Luft, J.; Ingham, H. (1955). "The Johari window, a graphic model of interpersonal awareness". Proceedings of the western training laboratory in group development. Los Angeles: University of California, Los Angeles.

Your lab has done a risk assessment, right? Right?