Cut up and leased out

“Just because they don’t have any next of kin doesn’t mean they have no voice.”

“Resurrections”

Railroads transformed America when the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, the first common carrier, was established in 1828. Transportation was revolutionized and the nation was connected. One unexpected connection was the rise of body snatching. Grave robbers flourished in Baltimore for over 70 years, driven by the demands of local medical schools for dissection materials. Baltimore became a hub for “resurrections,” as grave robbers called their trade, due to the proximity of multiple medical schools and the temperate climate that allowed for year-round digging, unlike the frozen grounds of New England and the Midwest.

Robbers typically began by breaking open a coffin, using hooks to extract the body, which was then concealed in whiskey barrels for transport, effectively masking the odor until reaching the medical school for dissection. The whiskey was then sold to all comers as “stiff drinks.” Ahem.

Grave robbing and body trafficking for profit were primarily Anglo-Saxon practices. In Central Europe, authorities typically allocated unclaimed bodies to medical schools, a system that was absent in the United States, England, and Scotland. As a result, medical schools in these regions resorted to obtaining dissection materials however they could. Paupers’ graves (called “Potter’s Fields”), criminals who’d been hanged, mental asylums, and even murder were all resources for fresh cadavers.

NBC News has been doggedly investigating patterns of ethical scandals involving cadavers in examples of modern-day “resurrections.”

Bodies Without Permission

Since 2019, under agreements with Dallas and Tarrant1 counties in Texas, the University of North Texas Health Science Center (UNT-HSC) received about 2,350 people whose bodies were ostensibly unclaimed. More than 830 of these bodies were selected by UNT-HSC for dissection and study. When the medical school was finished using the bodies for teaching and other groups for medical research, the bodies were cremated and buried or scattered at sea.

The problem was that some of those people had families who were looking for them.

Providing “unclaimed” or unidentified individuals for valid medical purposes has a long, if twisted, history and is a necessary component of teaching medicine and anatomy. It needs to be done ethically, however, or the central tenets of human rights and medicine are violated in the process of attempting to do good:

The new model for anatomy is indeed based on the recognition that anatomical dissection is only made possible through the selfless gift of another human being to the anatomist and student. With this acknowledgement, the anatomist and student are called to honor the individual who has made the gift in a dual manner: By using the donor’s body for the careful study of anatomy, and by allowing the donor’s body to serve as the focus of interpersonal relationships in life and death, to advance the humanistic culture of caring for those involved with the dissection, and inculcating the values of compassion, selflessness, kindness, and empathy within the practice of medicine.

The main takeaways from this scandal are:

Many of the families had never been contacted about their loved ones; some only learned after the body had been dissected and leased out (yes, leased out). Some of the families were refused the return of their loved ones, and were told by UNT-HSC that they’d have to wait, sometimes years, until the medical school was done using them.

It was about money, straight up. Using unidentified or “unclaimed” bodies saved Dallas and Tarrant counties about half a million dollars each year in cremation and burial costs. Many of these people are black, mentally ill, homeless, or whose families can’t afford cremation or burial. UNT-HSC medical school used some of the bodies for teaching but others were cut up and sent out for teaching and testing elsewhere—UNT-HSC was a procurement source for cadavers.

Those buying or leasing the remains did not know if or assumed that the proper permissions had been obtained. Once they found out, many have paused or stopped using UNT-HSC for this service.

This practice violates modern ethical guidelines.

NBC’s investigation led to the suspension of the body donation program and the firing of the employees who led it. UNT-HSC is bringing in outside consultants to investigate and review the program. Dallas and Tarrant counties are either suspending the process or canceling it altogether. As Tarrant county Judge Time O’Hare said, “No individual’s remains should be used for medical research, nor sold for profit, without their pre-death consent, or the consent of their next of kin.”

The UNT-HSC scandal is by no means the only one, just the latest in a torrid history of the disregard given to the dead, especially those of less than adequate means. Some individuals who donate their body to science still end up in unmarked graves.

Current Policies (or Lack Thereof)

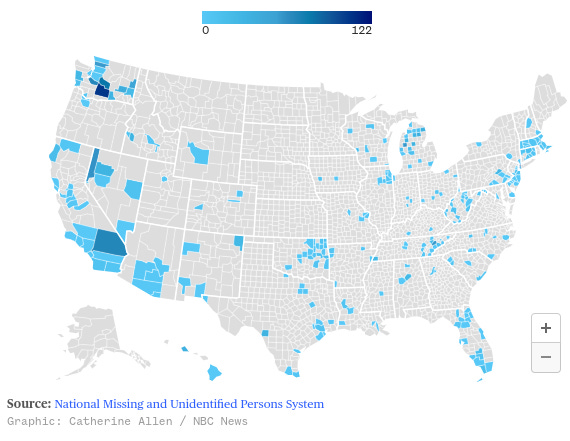

Many laws allowing for the use of unclaimed bodies remain on the books, but the medical community has largely moved beyond them. Some coroners and medical examiners have no written next-of-kin notification policies. The majority of them do not post the names of unclaimed dead to National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, or NamUs, the free federal database to resolve missing persons and unidentified remains cases. Anyone can view postings on NamUs and each listing is searchable on Google. There’s no reason not to use it. As NBC News reported, using NamUs would help reduce the misidentification and loss of loved ones:

Tens of thousands of bodies go unclaimed nationally every year, experts estimate, either because families cannot afford burials, the dead have no living relatives or because officials have failed to identify or reach next of kin. In many cases, the unclaimed dead were homeless or suffered from relationship-shattering addictions, making it difficult for officials to locate families.

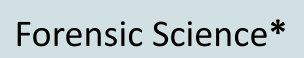

Number of unclaimed persons reports per 100,000 people

The vast majority of jurisdictions — shown below in gray — have not had a single unclaimed person report in NamUs over the past five years.

There is no nationwide mandate to use NamUs. Adoption of it by coroners and medical examiners is slow, despite a consistent campaign of information and presentations. It’s a hodge-podge of state adoptions:

Perhaps training would help the notification process; it is a stressful process for everyone involved. Even in professions where killing and the dead are routine, we have institutionalized the denial of death. Better communication between offices and agencies would help, as well: The police may be responsible for notifications but think the ME’s office has already done so.

Follow NBC News’ “Lost Rites” investigation

After a mother in Jackson, Mississippi, reported her son missing, police kept the truth from her for months.

‘They just threw him away’: Another Mississippi man was buried without his family’s knowledge.

America’s patchwork death notification system routinely leaves families in the dark.

The Department of Justice took action after a Mississippi coroner buried men without notifying their families.

The Jackson Police Department adopted a next-of-kin notification policy following NBC News’ reporting.

I worked at the Tarrant County Medical Examiner’s Crime Laboratory from 1992-1994.